We’re seeing a lot of positive movement across the energy landscape, especially regarding electric and gas utilities. There’s a lot of available funding and new policies being proposed and passed, highlighting energy efficiency as a major goal across the country. With opportunities beckoning and energy system improvements seemingly just around the corner, it can be hard to resist the urge to strike while the iron is hot. However, all communities in the Midwest will be unable to reap the benefits of energy efficiency without an intentional reflection on how these proposed energy system changes affect different customers and communities.

Energy Equity

First, it is imperative to recognize that the costs of the energy systems have not historically been equitably distributed across customers, notably leaving frontline and low-income communities with the brunt of these burdens. Rushing to implement energy system improvements without targeted efforts to address such inequities risks further alienating susceptible communities from the benefits of these energy efficiency opportunities. Energy equity centers efforts recognizing existing energy system burdens and designing policies, procedures and systems for a just distribution of energy system benefits (including health, economic and social benefits) for all communities.

Energy equity is divided into four different dimensions:

- Procedural – Who is at the table and what voice and power do they have in influencing planning, decision making and implementation?

- Distributional – Who bears the brunt of the burdens, who benefits, and how?

- Recognition/Structural– Who is vulnerable, who is privileged, and how?

- Restorative – How can we rectify past injustices caused by the energy system and prevent future harms?

As we move toward a more energy equitable future, it is imperative that we do not assess these dimensions haphazardly. Currently, foundations and frameworks are being developed to assess energy equity dimensions reliably and in ways that complement common practices across electric and gas utilities.

Benefit-cost Analysis

Benefit-cost analysis (BCA) is widely used by utilities and is “a systematic approach for assessing the cost-effectiveness of [distributed energy resource] investments by comparing the benefits and costs of alternative options”. However, BCA can often fall short when considering energy equity dimensions, especially distributional energy equity. Notably, BCA treats all customers within a jurisdiction as a collective, meaning there is no means to assess how the benefits and costs of options might vary across different groups of customers.

Distributional Equity Analysis

An emerging framework, the distributional equity analysis (DEA), looks to be an invaluable tool that addresses the equity shortcomings of BCA.

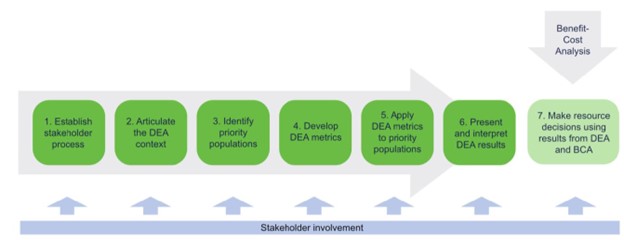

Let’s start with the basics. Distributional equity analysis is designed as a complement, NOT a replacement to BCA. A DEA serves as an effective complement to BCA because it separates customers into two groups: 1) priority populations and 2) all remaining customers. This distinction helps to identify the disparities in the distribution of the benefits and costs of existing or proposed investments across customers. DEA also includes a broad set of equity metrics, expanding the assessed costs and benefits beyond those seen in a BCA. Structurally, a DEA consists of seven stages, outlined in the figure below.

Stakeholder contribution throughout the entire process is critical for a high-quality DEA. Thus, it is imperative to recognize and attempt to remove barriers to stakeholder participation in a DEA. A few examples include providing relevant documentation, forms and captioning (where appropriate) in multiple languages, providing transportation to in-person meetings or holding virtual sessions to increase attendance, and recognition that there often might be a lack of trust between customers and regulators/utilities.

Distributional equity analysis does have some limitations. DEA only deals with one out of the four energy equity dimensions, so it cannot target or address issues related to the other three dimensions. DEA is limited in scope and focuses on improving the application of pre-existing analysis framework (BCA) on utility DER investments. While comprehensive assessment of all energy equity dimensions is possible via a system-wide equity assessment, these assessments are much broader in scope and require more time and resources to complete. Higher-impact changes to the energy system will need the meaningful inclusion and engagement of frontline communities in the development and implementation of energy programs and policies (energy equity dimension), highlighting that DEA is just a small, but important, step in the transformation of energy systems.

For greater detail on the steps of a DEA and best practices for implementation, I highly recommend the recently published guide on using DEA for DERs.